Business Email Compromise – one of cybersecurity’s costliest threats.

Business Email Compromise – one of cybersecurity’s costliest threats.

According to the Canadian Anti-Fraud Centre, Business Email Compromise scams are one of the most common types of fraud affecting Canadian businesses. Small businesses are particularly vulnerable to Business Email Compromise attacks because they may not have the same level of cybersecurity measures in place as larger businesses.

It is clear that small businesses in Canada are at risk of Business Email Compromise scams and other cyber attacks so it is important for these businesses to take steps to protect themselves, such as implementing strong cybersecurity measures, training employees on how to spot and avoid Business Email Compromise scams, and staying up to date on the latest threats and trends in cybercrime. Partek aims to help organizations better identify, understand, and manage the many forms of business email fraud they’ll likely face in the current work environment.

- According to the FBI Internet Crime Report, in 2020 alone, BEC schemes cost organizations and individuals more than $1.8 billion. That’s up more than $100 million from 2019, and it represents 44% of total cybercrime losses.

- In 2020, the Anti-Fraud Centre received over 6,800 reports of BEC scams in Canada, with losses totaling over $60 million.

- A report by the Canadian Federation of Independent Business (CFIB) found that 41% of small businesses in Canada reported being a victim of a cyber attack in 2020.

- The CFIB also noted that small businesses may be less likely to report cyber attacks due to concerns about reputational damage and the belief that reporting may not result in any action being taken.

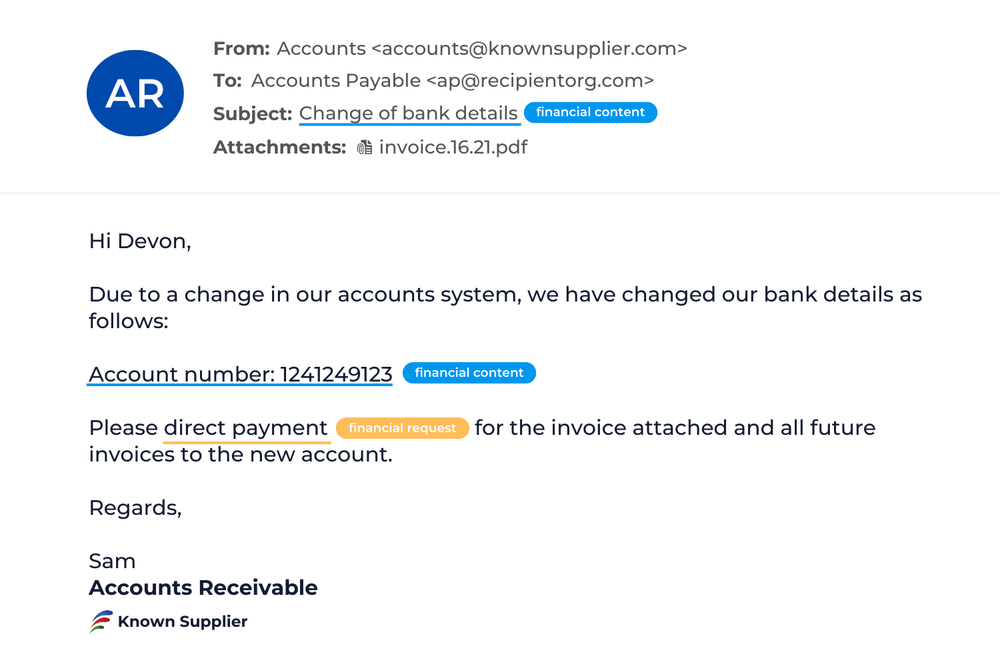

Invoicing Fraud

Invoicing fraud is an attempt to deceive someone into paying for products or services they did not purchase or redirecting a legitimate payment to the attacker’s account.

Invoicing fraud can arguably be one of the costliest business email compromises. Invoicing fraud transactions tend to be substantial and persistent, giving fraudsters ample incentive and opportunity to cash in.

What to look for?

- The subject lines of fraudulent invoice emails tend to be payment-oriented, making fake invoices appear genuine.

- Fraudulent invoices may feature company logos and professional formatting in order to appear more legitimate.

- The fraudulent email will likely include urgent language such as: “This invoice is 90 days past due and must be paid immediately.” Threat actors know that using threatening language encourages the recipient to act quickly – and think less.

- A fraudulent invoice can appear to be sent from anyone — a fellow employee or someone outside the organization. But the most successful ones exploit existing supplier relationships.

How it works

Impersonation: Supplier impersonation is a threat actor using common email spoofing techniques to pose as the supplier. Often, these fraudulent emails are sent from free webmail domains or unrelated compromised accounts the threat actor controls.

In many cases, an attacker may first impersonate the targeted company to get a real invoice from the supplier — then use that real invoice to turn around and impersonate the supplier.

Compromise: Supplier compromise involves a malicious actor gaining unauthorized access to a trusted supplier’s email account, then using that real account to scam the supplier’s customers. The attacker usually gains access to the account through a past phishing campaign or purchased credentials.

In many cases, attackers will piggyback an existing email thread of a compromised account. By observing, mimicking, and responding to actual conversations within the email thread, they can craft believable messages with supporting documents. Call it the ultimate impersonation tactic – becoming part of an active conversation. The recipient has no reason to suspect that the person they were communicating with has suddenly been replaced by an impostor. It’s no wonder these emails are among the most convincing BEC attacks most users will ever face.

Real World Example

In a supplier invoice fraud attack, an attacker tried to steal more than $100,000 from a company by posing as its usual wine supplier. The attacker had gained unauthorized access to the trusted supplier’s email account and hijacked an existing email thread between the customer and the supplier. The attacker requested a change in billing details and to send payment directly to a specified bank account. The email included a detailed invoice that featured the real supplier’s logo and legitimate charges to make it convincing. The attacker gained knowledge by using an existing email thread and included real invoicing numbers and products as to make the request more credible.

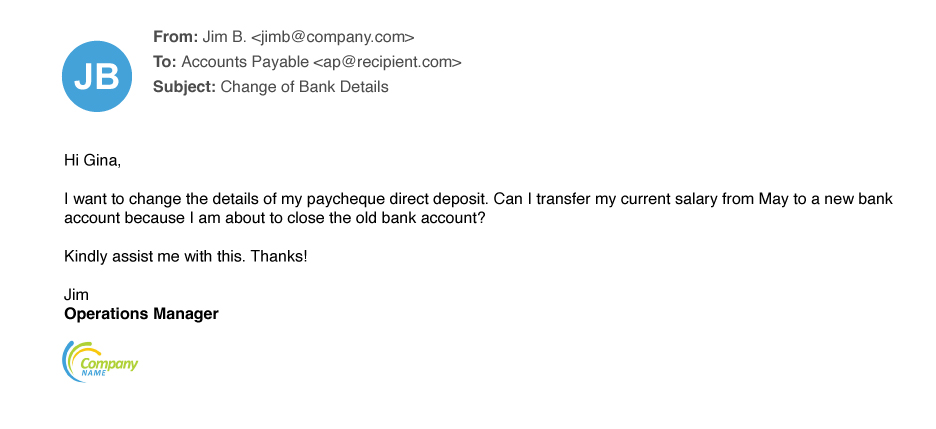

Payroll Redirects

Payroll redirects are among the simplest attacks we see. Whether they target finance, tax, payroll or HR departments, the goal is simple: trick the recipient into rerouting employees’ hard-earned wages — or even tax refunds — to the attacker.

According to the FBI, the average loss from payroll redirect attacks is $7,904 per reported incident. The IRS included payroll redirects on its “Dirty Dozen” list of tax schemes for 2020. The agency says attackers use IRS documents in payroll redirect schemes to convince recipients that fraudulent bank change requests are legitimate.

How it works

Payroll redirect schemes usually involve some form of impersonation. Typically, the threat actor utilizes display name spoofing so that the email appears to be from an employee. Some payroll redirects target higher-level executives and upper management for the chance to score a bigger paycheck. In these attempts, attackers may use email addresses with executive themes to lend credibility — eg. “[email protected]”.

Real World Example

One hallmark of payroll redirect schemes is their simplicity – a threat actor impersonates several employees in emails sent to a large company’s payroll department. Often emails use the same approach, differing only in: Who the email is sent to, who is being impersonated, the language used (English, German or Spanish). Despite the low-tech nature of these attacks, they can be surprisingly effective because they exploit a normal business process. Payroll, finance, tax and HR employees receive these kinds of requests by email every day, and most of them are legitimate.

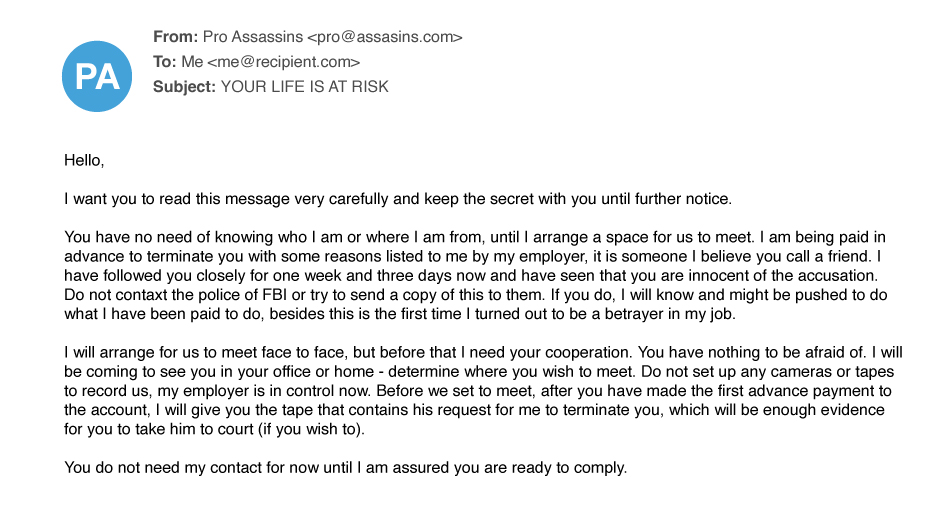

Extortion

An attacker threatens to destroy property, commit violence, or release confidential, embarrassing, or compromising information unless the recipient provides payment (typically through cryptocurrency) or something else of value.

How it works

Extortion email fraud uses just one deception tactic — impersonation. As in most impersonation-based attacks, the attacker will usually make the email look as if it originated from the victim’s email account. Typically, the threat actor sends a victim an email claiming to have accessed their computer and recorded them viewing adult content. The email includes sensitive content made to look like it came from the recipients’ own email account. Then threatens that the embarrassing content will be sent to co-workers and family, unless the recipients pay up.

Extortion has several subtypes:

- Data release: The attacker threatens to release sensitive, embarrassing, or compromising information; customer data or trade secrets; or evidence of criminal activity (whether real or not).

- Distributed denial of service (DDoS): The attacker threatens to overwhelm the recipient’s online operations with bogus traffic, making it inaccessible to legitimate users.

- Physical harm: This attacker threatens physical harm to the recipient or the organization. Common tactics include bomb threats, murder-for-hire plots, and other warnings of looming violence.

- Sextortion: The attacker threatens to release sexually related photographs or videos of the victim. Sextortion is probably the most common of these extortion subtypes.

Real World Example

Sextortion is by far the most common form of extortion we see. These emails tend to be lengthy and detailed, but the goal is simple: convince victims that they are in a precarious position and must meet the threat actor’s demands. Threats of physical harm are less common, though understandably alarming to the people who receive them. As seen in the email below, these strong-arm tactics try to scare the victims into thinking their lives are in grave danger unless they pay. Key attributes include a sense of urgency, short deadlines for complying, and dire warnings not to contact police.

Lures and Tasks

Lure or task emails are often the gateway to larger, multistage attacks that encompass other email fraud themes. A lure/task email gets the recipient’s attention, and the threat actor’s ultimate goal, such as payment redirects or invoice fraud, unfolds over time.

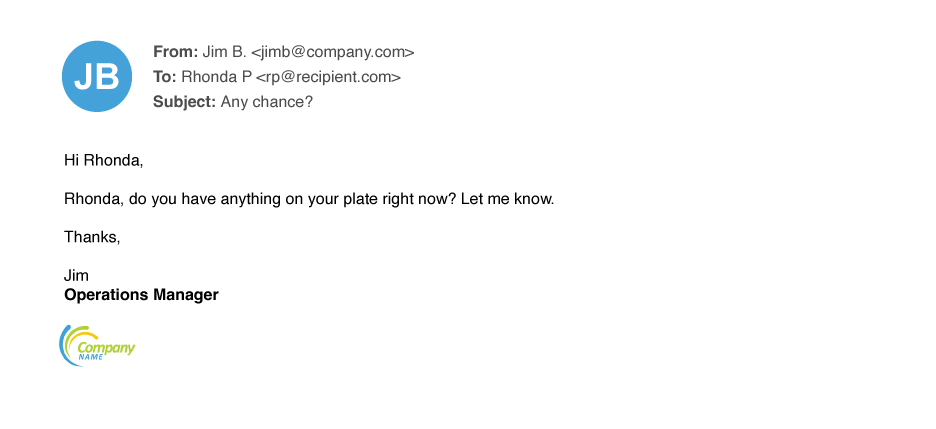

Lure and task emails often begin with a simple request or routine favor. While some attacks open with a specific ask, many are vaguely worded, reeling the victim in over the course of multiple emails.

How it works

An initial message might make a general request in the vein of:

- “Are you available?”

- “I need a quick favor”

- “Do you have a moment?”

Attackers commonly pose as someone the intended victim knows or trusts, such as an authority figures, close friend, or family member. Posing as someone familiar disarms any suspicions the recipient might have about an unexpected or unusual request and almost compels a response. Most lure/task emails use display name spoofing to deceive the recipient. Some use other impersonation tactics, such as spoofing the domain or reply-to addresses.

A simple response achieves the threat actor’s first aim: identifying an active email account and potentially receptive audience. After receiving a response, the threat actor often changes tactics to make the scheme seem more credible.

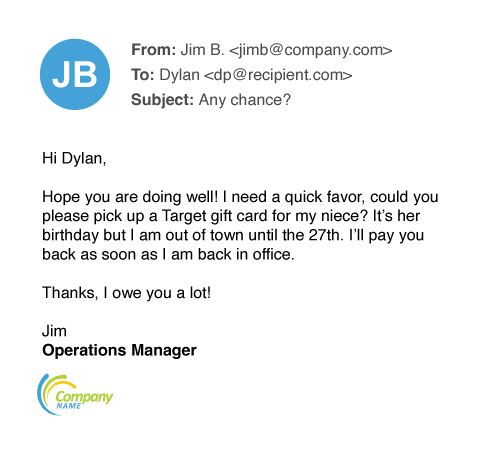

Real World Example

Many of the lure/task fraudulent emails we see begin with a brief email that gauges how receptive the target might be. These early emails may not even try to create a sense of urgency. Lure/task-themed email fraud is prolific, accounting for more than half the email fraud threats seen in 2021. Though these emails may seem benign at first, if the recipient falls for one, it can lead to more serious forms of email fraud with potentially costly outcomes.

Gift Carding

In gift carding schemes, attackers attempt to obtain payouts in the form of retail gift cards. Recipients are tricked into buying the cards and sending the numbers and PINs to the attacker, who then redeems or resells the cards.

These attacks work because companies often reward employees and partners with gift cards. To the recipient, the request might seem routine. If the email sounds urgent and offers a reasonable-sounding explanation, the recipient might act without giving it a second thought.

How it works

Attackers typically spoof a person in leadership or a position of authority to give the request legitimacy. As is the case with other forms of email fraud, posing as someone familiar, including close friends and family members, makes the recipient more likely to fall for the scheme. Most gift carding email fraud uses display name spoofing to deceive recipients. Sometimes, attackers use other impersonation tactics, such as spoofing the domain or altering the reply-to field.

Real World Example

Gift carding emails use all kinds of lures to make the request seem valid to the recipient: Threat actors may enlist everything from current events, such as the pandemic, to national holidays. Whatever the lure, the goal is to provide a plausible reason for the request and to elicit sympathy for the best chance of success.

Gift carding is a common form of email fraud. At an average $840 per incident, this crime has swindled people out of almost $245 million since 2018.

Sympathy for the scammer

The below example includes an attacker attempting to tug on the recipient’s heartstrings – the sender claims the request is for his niece’s birthday. In many cases, the threat actor first seeks to see whether the intended victim is available and the gift card request comes only after a person responds.Corporate gift card fraud

In this example, the threat actor spins a tale of wanting to get gift cards to distribute as an employee thank-you, a common corporate practice. In this case, the request is tied to the upcoming holiday season. This example shows that that some gift carding fraud starts with a brief lure and task email to test the receptivity of the potential victim.Advance Fee Fraud

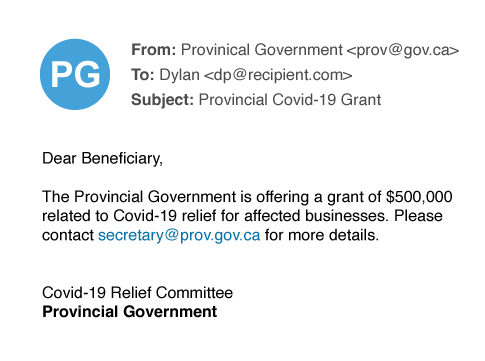

Advance fee fraud is an old con that is sometimes, and somewhat misleadingly, is called the “Nigerian prince” email fraud. It occurs when a threat actor asks the potential victim for a small amount of money in advance of a larger payout later. The requested funds are usually depicted as seed money to unlock or transfer the promised reward.

Attackers have dreamed up countless variations of advance fee fraud. They often weave elaborate tales of why a large sum of money is available and why they need a small upfront fee to get it to the email recipient.

Fraudsters often bait victims with subject lines that include:

- Inheritance

- Lottery winnings

- Awards

- Government payouts

- International business

Once the victim provides the advance fee, the fraudster may string the victim along for more money (citing unforeseen complications) or simply cut all contact and disappear.

How it works

Advance fee fraud uses impersonation techniques. Threat actors will commonly pose as a government officials, legal representatives, or persons in a dire situation. Most advance fee fraud emails use display name spoofing, though some use other impersonation tactics such as domain spoofing or lookalike domains.

Real World Example

Advance fee fraud emails use various lures to reel in victims, maintain their trust and persuade them to act. As shown in the following examples, threat actors may latch on to anything that works — including current events such as the pandemic, business deals, and beneficiary payouts. Most advance fee fraud emails are simple and easy to spot; few are well-crafted or more complex than the examples provided here. Advance fee emails make up a small fraction of fraud emails, still, people do fall for them, with an average loss of about $5,100 per incident.

This this example, the attacker tries to capitalize on COVID-19, urging the recipient to act quickly, giving the target little time to consider whether the email is fraudulent.

In this example, the attacker tries to tempt the victim with a large beneficiary payment, a common strategy in advance fee fraud that exploits human greed.

Conclusion and Recommendations

The types of email fraud outlined above are devious, unrelenting, and hard to manage with traditional perimeter-focused security tools and gateways.

Like most modern cyber attacks, they target people, not technology. That’s why stopping these attacks requires a people-centric approach.

Financial controls, such as requiring two or more people to approve changes to payment accounts or payroll details, is a good start. But stopping business email compromise also requires advanced email protection. To get more visibility into this human attack surface and stop business email compromise in all its various forms, you need a comprehensive platform with integrated controls across email, cloud accounts, users and suppliers.

Look for a solution that offers:

- Visibility into your human attack surface. You should understand who your most attacked users are, what and who attackers are targeting in your organization, and recognize which suppliers might be compromised or impersonated.

- Advanced detection capabilities to stop business email compromise, email fraud, and other threats that don’t employ malware. Email fraud uses social engineering and ever-evolving tactics that prey on human error. That means static rule sets, even when regularly updated, aren’t enough to identify and stop them. The best solutions also recognize factors such as suspicious email headers, the sender/recipient relationship, and the sender’s reputation. Look for vendors with large, diverse data sets, and human threat expertise.

- The ability to prevent attackers from commandeering users’ accounts and using them for email fraud attacks. As more businesses move to the cloud, protecting against email fraud also means protecting cloud accounts. Look for tools that prevent your users’ accounts being commandeered for email fraud attacks.

- Security awareness training that augments technical controls. With the right education, especially when it’s based on real-world threats, you can turn users into a strong last-line of defense. Make it easy for users to report suspicious messages and for your security team to verify them with automated analysis and remediation.

Totally overwhelmed?

Let Partek's team of Information Technology Professionals handle it for you.

Resource: Proofpoint